LIBRARY AND EARLY WOMEN'S WRITING

WOMEN WRITERS

Eliza Haywood (c.1693-1756)

by Ruth Facer

Very little is known for certain about Elizabeth (Eliza) Haywood's life. For a long time, it had been generally accepted that Haywood was the daughter of Robert Fowler, a small shopkeeper, and his wife Elizabeth, probably born in London in 1693. Recently, however, Christine Blouch's research has presented interesting new information on Haywood's life.[1] She has offered alternative parentage for Haywood, proposing a Francis and Elizabeth Fowler, whose daughter was christened on 14 October 1693. Haywood herself suggested a third possible identity when she claimed that she was a near relative of 'Sir Richard of the Grange'. As Blouch demonstrates, Richard Fowler of Harnage Grange, Shropshire, had a sister Elizabeth, and his daughter Elizabeth was christened on 13 January 1692/1693. Whoever her parents were, Haywood must have received a good education, as she grew up able to translate works of fiction from French into English.

The question of Haywood's marriage is equally contentious. Until recently, her husband was thought to have been the Reverend Valentine Haywood, a middle aged clergyman, deserted by his wife. The cleric placed an advertisement in the Post Boy for 7 January 1721, disclaiming responsibility for his wife's debts, a common practice in cases of missing wives. Blouch has not found sufficient evidence to uphold the long established view that the runaway wife was Eliza. Instead, Blouch proposes that Eliza Haywood might have been a widow, citing a single reference she made to the death of her husband. There is further dispute upon the question of how many, if any, children Haywood had. Blouch suggests that she had two, and that they were almost certainly both born out of wedlock.

Eliza Haywood's life on the stage probably started in Dublin at the Smock Alley Theatre in 1714, and later continued in London until 1737 when theatres were closed by the Licensing Act. Her theatrical career was varied and was not confined to appearances on the stage. An attribution made in the 1990s named her as the author of The Dramatic Historiographer, or, The British Theatre Delineated (1735), a popular survey of the British theatre.[2] She also took up her pen and wrote plays for the Theatre Royal in Drury Lane, and the Lincoln's Inn Fields Playhouse (such as The Fair Captive, [1721]), translating French and Spanish dramas, and rewriting others. One of these, in which she collaborated with William Hatchett, who was thought to have been her lover, was an operatic rendering of Tom Thumb the Great alter'd from the Life and Death of Tom Thumb the Great, and Set to Musick after the Italian Manner (1733). It is Haywood at her very worst. Doodle (the other courtiers are Noodle and Foodle) describes the hero thus:

'Tis whisper'd in the books of all our sages,

This mighty little hero,

By Merlin's art begot,

Has not a bone within his skin,

But is a lump of gristle.

Eliza Haywood could write better than that. Happily, she is better remembered as a prolific and influential early eighteenth-century novelist, producing approximately sixty-one works of fiction (numbers vary according to the biographer), most were published anonymously. Between 1720 and 1730 alone she published thirty-eight works, most of which were written in an early form of the novel commonly referred to as the romance. Her subject was usually 'amatory' fiction, narratives of desire focussing on highly charged sexual episodes, concerned with love and seduction in all their guises. Phrases such as 'the present burning Eagerness of Desire' and 'the wild Exuberance of his luxurious Wishes' (Fantomina, [1725]) illustrate the lavish language she often used. Virginity was frequently lost either through rape or reluctant surrender, fortunate heroines were married off, while others were banished to a nunnery. The best known of Haywood's earlier works, and the first of her prose fictions, is Love in Excess (1719), a highly successful bestseller in its time, which went into several editions. It is a multi-volume work, longer than most of her novellas of this period of her career. The plot concerns Count D'Elmont, a mixture of hero and determined rake, and moves from one seduction or near seduction to another. Amorous intrigue and counter-intrigue interweave until the hero is ultimately reformed and marriage is his final destiny.

A versatile writer, Eliza Haywood also wrote in the form of masquerade novels, including The Masqueraders: or, Fatal Curiosity: Being the Secret History of a Late Amour (1724-5), in which mask and clothing disguise characters who would otherwise know each other only too well. One of the best known of her works of fiction in this form is Fantomina (1725), a novella. The story is of a 'young Lady of distinguished Birth, Beauty, Wit, and Spirit' who maintains the attention of Beauplaisir, a young rake with a roving eye, by donning a series of different guises. With each new persona, she allows herself to be seduced. Inevitably, she ends up having a child, but not before her mother appears upon the scene and sends her off to a 'nunnery' in France in disgrace.

Although popular with her reading public during this early period of the 1720s, Eliza Haywood was berated by some of her literary contemporaries for writing scandalous and licentious books, in which the identities of court figures and private individuals were sometimes only thinly veiled. In a note to the Dunciad (published in 1728 and expanded in 1742) Pope described her as one 'of those shameless scribblers (for the most part of that sex which ought least to be capable of such malice or impudence) who in libellous Memoirs and Novels reveal the faults and misfortune of both sexes, to the ruin or disturbance, of public fame or private happiness.' Again in the Dunciad, Haywood is offered as the prize in a urinating competition: 'Who best can send on high/ The salient spout, fairstreaming to the sky,' (II, 15.3-5). The second prize was a chamber pot. Pope also gave what may be the only, very unflattering, pen portrait of Haywood, 'yon Juno of majestic size/ With cow-like udders, and with ox-like eyes.' Swift too wielded his pen against her and wrote to Lady Suffolk, 'I have heard of [her] as a stupid, infamous scribbling woman.'

Haywood wrote very little fiction during the 1730s. She was possibly subdued by stringent criticism, although scholars tend to feel that she may have published less in this period because she was receiving income from the theatre. Her literary output increased again during the latter part of her life in the 1740s and 1750s until her death. By this time she had become a member of the publishing trade and had opened a bookseller's shop under the Sign of Fame in Covent Garden in 1741. She only kept the business for a year, although she continued to act as a distributor of books and pamphlets.

Not only a dramatist, novelist and poet, Eliza Haywood was also a periodical editor. In the 1720s, she had produced The Tea Table and is sometimes credited with the editorship of The Parrot. In 1746 The Parrot briefly re-emerged for a run of nine weeks, undoubtedly under Haywood's editorial eye this time, addressing burning political issues and topical concerns, including the '45 Rebellion and the cause of the Young Pretender. Her best known periodical publication, however, was The Female Spectator, which appeared monthly from April 1744 to May 1746. One of the first, if not the first, periodicals written by a woman for women – it is widely held that Mary Delariviere Manley, Haywood's contemporary, was the author of The Female Tatler (1709) – it contained both frivolous and romantic tales as well as essays on political subjects, science and war. Advice was given on how to manage husbands and other issues concerning the daily round. There is even some attempt at amateur psychology. In one issue of the magazine, a lonely widow is described and her behaviour analysed. One should examine, 'at what Point of Time this Aversion to Solitude commenced: If from Childhood, and so continued even to the extremest old Age, it can proceed only from a Weakness in the Mind, and is deserving of our Compassion.' By this period of her career, Haywood was claiming to be a reformed character and, in the guise of her authorial persona, admitted in the opening instalment of The Female Spectator, that 'My Life, for some Years, was a continued Round of what I then called Pleasure, and my whole Time engross'd by a Hurry of promiscuous Diversions'.

On the surface, Haywood's best-known work of fiction from this period, The History of Miss Betsy Thoughtless (1751) reflects her new moral stance. Or does it? There is a tantalizing ambiguity in Haywood who was, after all, a businesswoman in the literary world. Was her so-called reform her way of capitalizing on the shift in literary fashion away from amorous intrigue to sentimental tales in which virtue triumphed? The sex and excitement is still there in the tale of a feckless young girl, let loose on the fashionable London world. Miss Betsy, the heroine, enjoys courtship and pursuit, which she allows to go as far as possible without losing her virginity; she eventually marries the wrong man. Only after miserable trials of male dominance, miserliness and infidelity on the part of her husband, is she able to marry Mr. Trueworth, the man she really loves. Virtue triumphs in the end. Betsy, the coquette, has learnt from her experiences and she has become a reformed character. She realises that 'not one action of my life has given any proof of common reason'.

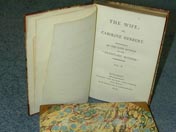

The History of Miss Betsy Thoughtless is a delightful mixture of light and shade. The heroine romps between one dangerous and titillating incident to the next for much of the book, but there is a more serious side, which has given a lasting importance to the work. Haywood, herself the victim of an unhappy marriage, vividly portrays the repression of eighteenth-century women within the bounds of wedlock with insight and detailed analysis. Betsy's darkest moment came as she reflected 'that it was by death alone she could be relieved from the vexations which she was threatened with from a man of his humour' and was racked 'with the most terrible revulsions.' Death came to her rescue, but even then social mores prevailed: 'I lament him as one who was my husband, whom duty forbad me to hate while living, and whom decency requires me to mourn when dead.' The novel is further important as it is the first in a long line of fiction in which the heroine can only marry the man she loves after she has painfully learnt from her mistakes, and has begun to grow up. This theme was revisited by such writers as Charlotte Lennox (The Female Quixote), Frances Burney (Evelina) and Jane Austen (Emma). The History of Miss Betsy Thoughtless was popular and well reviewed, and Eliza Haywood had become a respectable novelist. She continued to write works of moral advice, such as The Wife and The Husband In Answer to the Wife (both published in 1756) until her death in 1756.

Eliza Haywood died on 25 February1756, writing to the end and apologizing in the last issue of The Young Lady, her new weekly periodical for women, that she was too ill to continue writing; she was buried at St. Margaret's Church, Westminster. An important, popular and colourful writer, Haywood deserves the revival of interest which she has today. She may have been reviled in her time, especially during her early career, but in recent years her fortunes have begun to change. She is named in well over one hundred sites on the Internet and the number of University courses, research papers, critical works, and new editions of some of her own writings are evidence enough of the growing interest in her, and the appreciation of the best of her work. At least twenty-five of her titles are available in modern editions. She is now viewed as one of the most important women writers, of the early eighteenth century. Eliza Haywood will live on too, like Frances Burney, for some of the words she coined. According to the Oxford English Dictionary News (September 2026) she was the first to talk about the 'middling class', to refer to a person's final 'resting-place' and to use the word 'poignancy'. She visited a 'habit-shop', worried that the colours in her table-cloth might 'run' and used a 'pig-iron' for her cooking. Above all, whether in fiction or in social and political commentary, she did her best to make the voices of women heard.

Select Bibliography of Haywood's Works

Love in Excess, or the Fatal Enquiry (London: W. Chetwood and R. Francklin, 1719)

The Fair Captive: A Tragedy (London T. Jauncy and H. Cole, 1721)

The British Recluse: or; The Secret History of Cleomira, Suppos'd Dead (London: D. Brown; W. Chetwood; and J. Woodman; and S. Chapman, 1722)

The Injur'd Husband or the Mistaken Resentment. A Novel (London D. Brown Junr., W. Chetwood, J. Woodman and S. Chapman, 1722)

The Wife to be Lett: A Comedy (London. Dan. Browne Junr. and Sam. Chapman, 1724)

Lasselia: or, the Self-Abandon'd. A Novel (London D. Browne Junr. and S. Chapman, 1723)

Idalia: or, the Unfortunate Mistress (London: D. Brown Junr., W. Chetwood and S. Chapman, 1723)

Memoirs of a certain Island adjacent to the Kingdom of Utopia (London: [n. pub.], 1725)

The Rash Resolve: or, the Untimely Discovery. A Novel (London: D. Browne Junr, and S. Chapman, 1724)

The Tea Table (London: J. Roberts,1724)

Memoirs of Baron de Brosse,Who Was Broke on the Wheel in the Reign of Louis XIV (London: D. Browne and S. Chapman, 1725-1726)

The Masqueraders; or, Fatal Curiosity: being the secret history of a late amour, part I (London: J. Roberts, 1724), part II (1725)

Fantomina: or, Love in a Maze, being a Secret History of an Amour between Two Persons of Condition (London: Dan. Browne amd S. Chapman, 1725)

The City Jilt: or, the Alderman turn'd Beau (London: J. Roberts, 1726)

The Mercenary Lover, or, The Unfortunate Heiresses...Being a true secret history of a City amour in a certain island adjacent to the kingdom of Utopia (London: N. Dobb, 1726)

The distress'd orphan, or, Love in a mad-house (London: 1726)

The Secret History of the Present Intrigues of the Court of Caramania (London: [n. pub.], 1727)

Philidore and Placentia: or l'Amour trop delicat (London: J. Roberts,1727)

The Fruitless enquiry. Being a collection of several entertaining histories and occurrences, which fell under the observation of a lady in her search after happiness (London: J. Stephens, 1727)

The Life of Madam de Villesache (London: J. Roberts, 1727)

Frederick, Duke of Brunswick-Lunenburgh. A tragedy (London: W. Mears, J. Brindley, 1729)

Eliza Haywood and William Hatchett, The Opera of Operas; or, Tom Thumb the Great. Alter'd from the Life and Death of Tom Thumb the Great (London: J. Roberts, 1733)

The Adventures of Eovaii, Princess of Ijaveo. A Pre-adamtical history. Interspersed with a gret number of remarkable occurences (London: S. Baker, 1736)

A Present for a Servant-Maid; or, the Sure Means of Gaining Love and Esteem (Dublin: George Faulkner, 1743)

The Fortunate Foundlings: being the genuine history of Colonel M-rs, and his sister, Madam Du P-y (London: T. Gardner, 1744)

The Female Spectator (London: T. Gardner, 1744-6)

The Parrot. With a Compendium of the Times (London: T. Garnder, 1746)

Life's Progress through the Passions: or, The Adventures of Natura (London: T. Gardner, 1748)

Epistles for the Ladies (London: T. Gardner, 1749-1750)

The History of Miss Betsy Thoughtless, 4 vols (London: T. Gardner, 1751)

The History of Jenny and Jemima Jessamy, 3 vols (London: T. Gardner, 1753)

The Wife (London: T. Gardner, 1756)

The Husband. In Answer to the Wife (London: T. Gardner, 1756)

- Christine Blouch, 'Eliza Haywood and the Romance of Obscurity', SEL 31 (1991), pp. 535-551.

- The attribution by Marcia Heinemann is confirmed by Blouch and is referenced in David Oakleaf's introduction to Love in Excess, by Eliza Haywood (Peterborough [Ontario]: Broadview literary texts, 1994).

< Back | |